On Reading The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe to My Six-Year-Old

The struggle, the meltdown, and the triumph

My daughter and I have been reading The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe together nearly every night for the last month or so. It’s been slow going and, honestly, a bit rocky at times. Published in England in 1950, the book is full of words and expressions completely foreign to a child born in America in 2018. When the child in question has a tendency to respond with explosive frustration anytime she doesn’t fully understand something right away, reading a book like this can present some challenges, to put it mildly.

Case in point: a few nights ago, finally approaching the climax of the book, we spent a good 15 minutes going through a single paragraph spoken by the White Witch to Aslan:

“Tell you what is written on that very Table of Stone which stands beside us? Tell you what is written in letters deep as a spear is long on the fire-stones on the Secret Hill? Tell you what is engraved on the scepter of the Emperor-beyond-the-Sea? You at least know the Magic which the Emperor put into Narnia at the very beginning. You know that every traitor belongs to me as my lawful prey and that for every treachery I have a right to kill.”

Spear, fire-stones, engraved, emperor, scepter, traitor, lawful, prey, treachery. All unfamiliar words for her. Each one had to be explained and then explained again and then once more. Voices were raised. Tears were shed. Meltdowns escalated. My daughter wasn’t too happy either. ;-)

As I tucked her in that night, I worried it had been a bad idea to read this book. I wondered if we shouldn’t take a break and come back to it when she’s a bit older. I wanted to instill in her a love of reading and was afraid I was sabotaging that goal by insisting on a book that was so demanding.

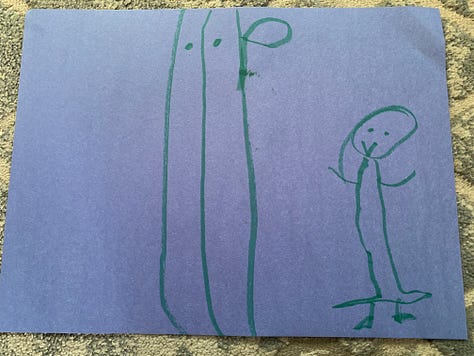

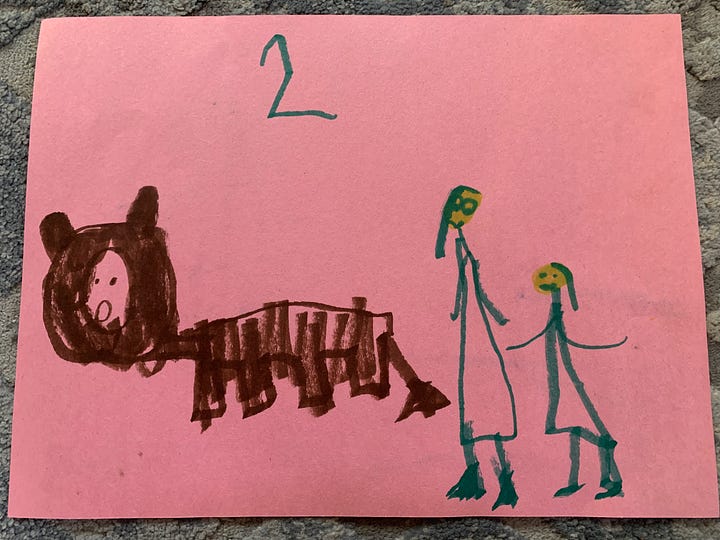

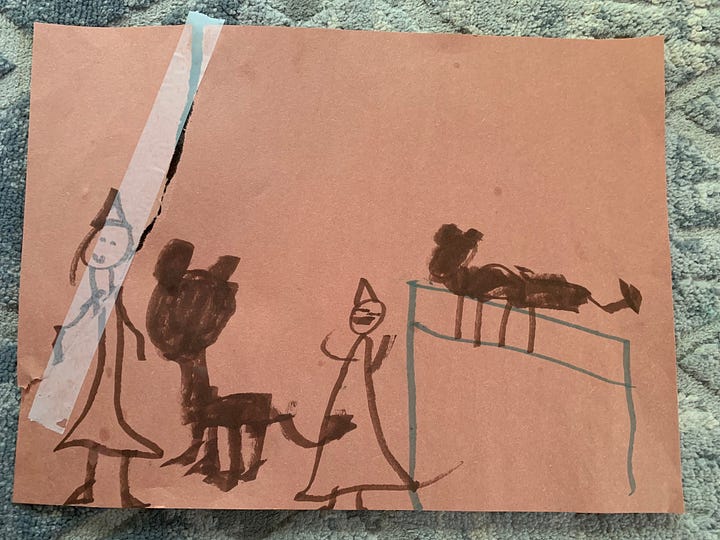

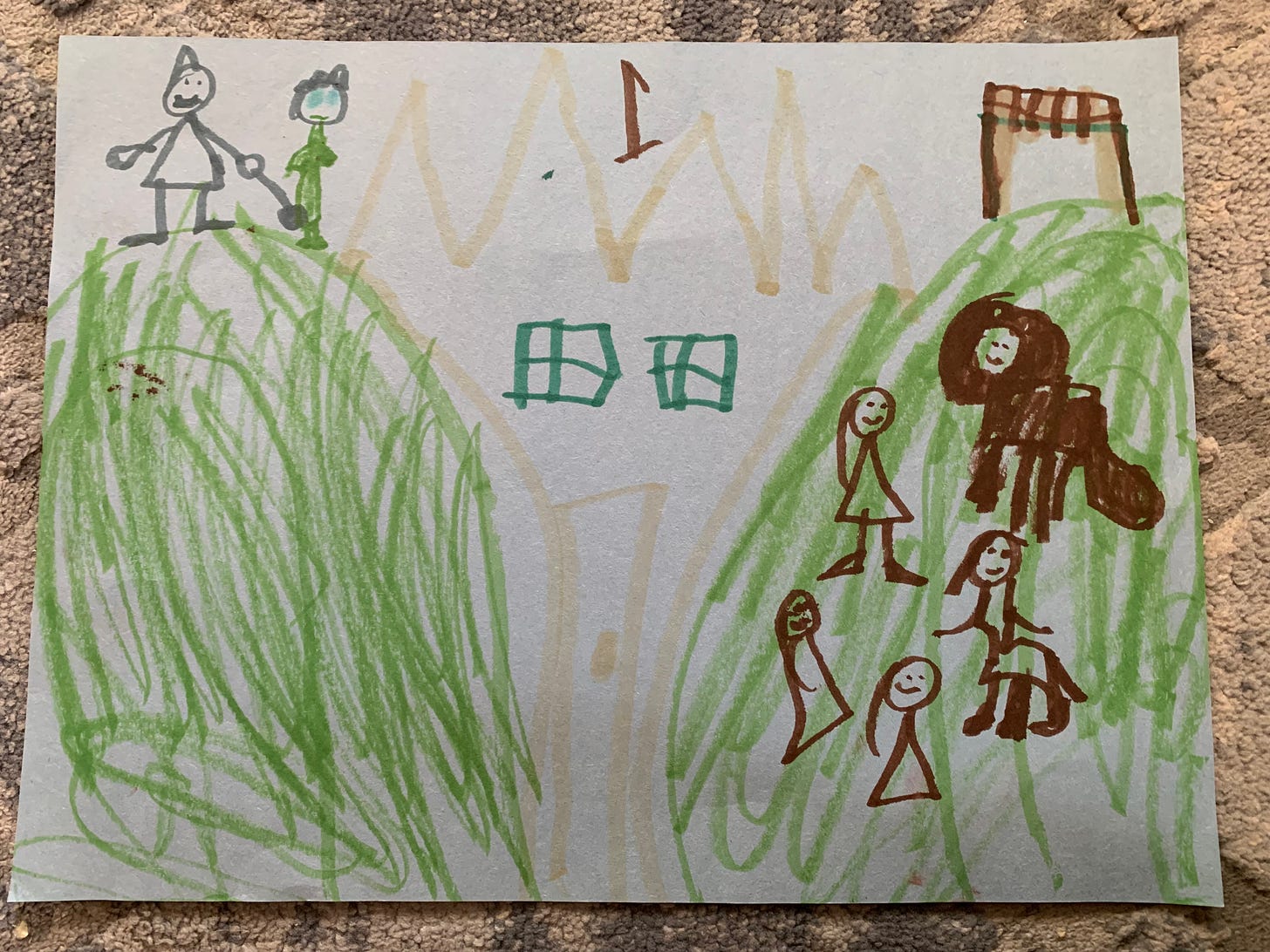

But then the next evening she asked to read the book again, and so we kept going, slowly. A few days after that, when she was supposed to be doing her homework (why is there so much homework in first grade? A question for another day…), I found her on the floor of the dining room with a box of markers, hunched over piles of construction paper. She was drawing pictures of the places, characters, and events of the book:

I was stunned. How many times had she shouted in frustration, “I don’t understand anything that’s going on in this book!”? But she did understand, even with all the big words, the unfamiliar, old-fashioned British lingo, the lengthy, formal speeches, and the many descriptive passages. Somewhere along the way, things started clicking for her, and she was hooked. In fact, I think she’s understanding this book better than many things we’ve read—perhaps because unlike most children’s books published nowadays, which are vapid, inane, or both (sorry but it’s true), there’s actually so much to understand in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.

It also showed me something so beautiful about slow reading. When you read a book over a period of days or weeks, it’s like being in an extended conversation with the author. Reading doesn’t just happen when you’re looking at the words on the page (or having them read to you). It happens in the many hours in between as well. Even when the book is closed, your imagination continues to process what you read. Your mind draws connections between the book and things going on in your daily life, conversations you have, other books you’ve read in the past—all of it.

“When we pass over into how a knight thinks, how a slave feels, how a heroine behaves, and how an evildoer can regret or deny wrongdoing, we never come back quite the same; sometimes we’re inspired, sometimes saddened, but we are always enriched. Through this exposure we learn both the commonality and the uniqueness of our own thoughts—that we are individuals, but not alone,” writes Maryanne Wolf.

Reading The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe with my six-year-old has shown me that children are equipped to handle material that is so much more complex and rich than what our culture pushes on them these days in the form of YouTube shorts, dopamine-triggering video games, and even, sadly, many of the fluffy, condescending books you’ll find on display in the children’s section of a typical library. Not only are they equipped to handle more; I think they crave more. It’s up to us to give it to them.

The only question is: what should we read next?

Now get the rest of the books in the Chronicles of Narnia series and read them to her. I cannot even recall how many times I read these books to my kids when they were little. At least 5 or 6 times! Then they started reading them themselves. No idea how many times.

This was so great, Christina -- I especially loved how you highlighted how you're able to process and make connections when you read slowly. ("Sleeping on it" feels underrated nowadays!)

I'm not sure if your final question was rhetorical or not (haha), but if you're looking for a chapter book, maybe try Charlotte's Web :) I love this quote from E.B. White about writing for children:

"Anyone who writes down to children is simply wasting his time. You have to write up, not down. Children are demanding. They are the most attentive, curious, eager, observant, sensitive, quick, and generally congenial readers on earth....Some writers for children deliberately avoid using words they think a child doesn’t know. This emasculates the prose and, I suspect, bores the reader. Children are game for anything. I throw them hard words, and they backhand them over the net. They love words that give them a hard time, provided they are in a context that absorbs their attention."